Pride and Consequence

The room smelled of old wood, spilled beer, and sweat — a backstage afterparty the way they used to be before everything got big and bright and fake. Baton Rouge air pressed against the walls, thick and heavy, the kind of heat that made a man want to take off his skin and sit a while.

John Fogerty leaned against a scratched-up bar table, arms folded. He wasn’t drinking, not really. Nursing a single beer so nobody would hassle him. He wasn’t here to party — he hated these things — but an old friend had begged him to come out, just to shake a few hands.

It had been a bad few years. Legal battles, endless lawsuits with Fantasy Records. Being treated like a ghost at his own funeral while lesser men smiled for cameras.

He missed playing, sure. But he didn’t miss this circus.

A commotion at the door. A cluster of roadies and promoters parted like drunks around a fire hydrant.

In stumbled Ronnie Van Zant — barefoot, of course, his hat tipped too far back on his head, a beer already half-drained in his hand. Behind him, like a shadow, trailed his little brother Johnny — all bravado and loudmouth swagger, a fake country-boy grin pasted on.

“Shit,” Fogerty muttered under his breath. He knew the type. Loved their people but not smart enough to see the chains tightening. Proud in all the wrong ways.

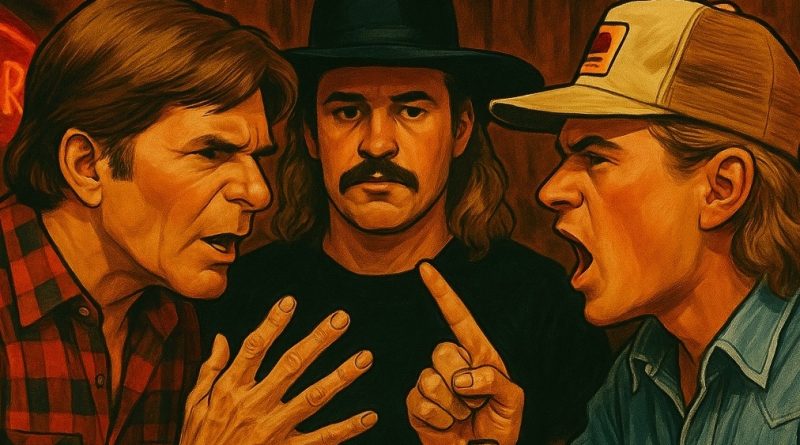

Someone, probably a promoter, shoved Ronnie forward like a prizefighter toward Fogerty.

“John! Ronnie Van Zant! You two legends oughta meet! Same cloth, right?”

Ronnie stuck out his hand, grin wide, eyes a little glassy but sharp beneath the haze.

“Man, I grew up singin’ ‘Proud Mary’ in every backwoods bar from here to Tupelo,” Ronnie said. His voice was a cracked window, letting in warmth and old bruises.

John shook his hand — firm, cautious. “Appreciate it,” he said, voice even.

Johnny came in behind him, braying like a donkey.

“Betcha California boy here don’t even own a gun!”

Laughter from a few sycophants at nearby tables.

Fogerty felt the familiar coil of anger in his gut. He could have let it slide. Maybe he should have. But the years had worn him thin.

He smiled — a cold, cutting smile.

“I write songs about rich boys sending poor boys to die, son,” he said, his voice low and sharp. “You’d know about that if you listened instead of running your mouth.”

The table went still. Even Ronnie winced.

“Aw hell,” Ronnie said, stepping between them, arms raised in mock surrender. “Ain’t no call to start talkin’ politics, boys. We’re here to drink, not to fight.”

Fogerty didn’t back down. He fixed Ronnie with a look that had nothing to do with drink or party games.

“Politics are life when you’re broke and bleeding in a rice paddy,” he said. “Or working two jobs so some clown in a suit can buy a third yacht. You boys sing about pride like it’s a tattoo you’re born with. It ain’t. It’s something you fight for. And it sure as hell ain’t free.”

Johnny snorted, trying to wave it off, too dumb or too drunk to read the room.

“Damn right! We work hard for what we got! Ain’t nobody handed us nothin’!” he crowed, slapping Ronnie on the back.

Fogerty’s eyes narrowed. He stepped closer, voice dropping to something that could cut leather.

“Sure,” he said. “Except Daddy’s loans. Mama’s Buick. Pretty good start for a bunch of poor boys.”

The words landed hard.

Ronnie’s face twitched — not anger at Fogerty, but something deeper, like a bruise pressed too hard.

Because he knew.

Ronnie had worked roofing jobs, had eaten shit for years. But he knew Johnny played the good ol’ boy card too hard, knew the difference between real pride and costume pride. And it gnawed at him in ways he’d never say out loud.

Ronnie slammed his beer on the table. Foam spattered.

“It ain’t about money,” he said, voice hoarse. “It’s about where you’re from. It’s about holdin’ up your people, even if they ain’t perfect. ‘Cause if we don’t, who the hell will?”

Fogerty stared at him for a long moment.

Then he said, soft and sad,

“Then you better make damn sure you’re lifting them up — not chaining them to the past ’cause you’re too scared to let it go.”

The air between them turned heavy.

Johnny cracked some dumb joke about “too many tree-huggers in here” and wandered off to find another drink. A few of the hangers-on peeled away with him, grateful for the excuse.

Ronnie stayed a moment longer. The mask slipped. He looked older, more tired than the rock star everybody knew. For a second, Fogerty could see the boy who’d once climbed roofs in July to pay for guitar strings.

Ronnie shook his head slowly.

“Ain’t as easy as you make it sound, John,” he said. His voice cracked like old wood.

“Ain’t as easy when it’s your people.”

Fogerty wanted to answer — wanted to tell him that pride and love weren’t the same thing, that loyalty without honesty was just a different kind of noose — but he didn’t.

Some things a man had to learn on his own.

He just nodded, and Ronnie nodded back. No handshake. No hard feelings. Just two tired men walking different roads.

Ronnie turned and followed his brother into the crowd.

The noise swallowed him up like a tide.

Fogerty finished his beer and walked out into the heavy Louisiana night, the air so thick it felt like ghosts pressing against his skin.

A few weeks later, the plane would go down.

And Ronnie’s road would end in a burning field in Mississippi.

Fogerty would remember that night sometimes — the way Ronnie’s voice broke, the way pride and pain fought each other behind his eyes — and wonder how many more Southern ghosts the country could bury before it learned anything at all.

Nice. You have taken whatever genetic gift I have contributed to and made it into something meaningful. Your Gran would be so proud of you being as I was so lackadaisical in application of what she gave to me to me to give to you.