Introduction: Beer’s Cybernetic Vision and Its Modern Relevance

Though his name might be unfamiliar, Anthony Stafford Beer (1926–2002) profoundly shaped modern thinking about how organizations, economies, and societies can function more effectively and humanely. In the early 1970s, Beer was invited by Salvador Allende—the world’s first democratically elected socialist president—to help design an alternative to both capitalist markets and Soviet-style planning. The result was Project Cybersyn, a bold attempt to manage Chile’s economy in real time using computer networks, feedback systems, and participatory decision-making. It remains one of the most ambitious experiments in cybernetic governance ever attempted.

Beer was a pioneering theorist of management cybernetics—what he called “the science of effective organization”¹. His work, spanning seminal books like Brain of the Firm (1972), The Heart of Enterprise (1979), Platform for Change (1975), and Designing Freedom (1974), applied the principles of cybernetics—feedback, communication, and control in complex systems—to businesses, governments, and entire societies. His career ranged from optimizing corporate operations in postwar Britain to helping Chile’s socialist government rethink economic management through a scientific, decentralized lens². Throughout, Beer retained a consistent humanist vision: he believed modern technology could—and must—be used to enhance human freedom and well-being, not to constrain them³.

Half a century later, Beer’s ideas remain strikingly relevant. Many institutions today still struggle with complexity and scale—issues Beer tackled head-on. We live in an era of corporate “efficiency” drives, unprecedented capitalist reach, renewed debates about socialism, political gridlock in governance, and breakneck technological change.

Through this article, I’d like to revisit Stafford Beer’s body of work and legacy to explore five big questions:

- Rethinking Efficiency: How does Beer’s work challenge or even disprove modern notions of corporate “efficiency”?

- Perils of Unfettered Capitalism: How does his work warn of the dangers of capitalism left unchecked?

- Cybernetic Socialism: How does Beer provide a rigorous, scientific-materialist argument in favor of socialist organization of society?

- Governance and Subordination of Corporations: How could Beer’s principles be applied to American governance (local, state, federal, and corporate), and what structures would ensure corporations remain subordinate to democratic government?

- Updating Beer’s Ideas: Which aspects of Beer’s work need updating in light of today’s technological, political, and economic developments to keep them relevant?

We will tackle each in turn, drawing on Beer’s writings and modern analyses, with an eye toward clarity. Stafford Beer’s ideas were ahead of their time – and today, we have new tools and perspectives to evaluate them. As Beer himself wrote in Platform for Change, society’s true goal should be eudemony (human flourishing); money and short-term metrics should be mere means to that end4. It’s a message that resonates now more than ever.

1. Challenging “Efficiency”: Beer’s Critique of Corporate Orthodoxy

Modern corporations exalt efficiency – often defined narrowly as maximizing output or profit while minimizing costs and slack. In practice this can mean rigid hierarchies, strict rules, and relentless cost-cutting (downsizing staff, squeezing suppliers, etc.) in pursuit of short-term gains. Beer’s work argues that this conventional notion of efficiency is not only misleading but actually destructive to an organization’s long-term viability. True efficiency, in Beer’s view, requires adaptability, resilience, and the full creative engagement of people – qualities that rigid, high-pressure systems often sacrifice.

Limited Views of Efficiency vs. Viability: Beer distinguished between making a system appear efficient in the short run and ensuring it remains viable (able to survive and thrive) in the long run. A hallmark of Beer’s approach is the idea that complex systems (like firms or economies) must handle variety, i.e. the range of different situations or disturbances they face. “Efficient” organizations often try to simplify or constrain this variety to manageable levels – for example, by imposing top-down controls, standard operating procedures, and by eliminating any excess capacity or flexibility. Beer showed that while such measures reduce complexity and can boost efficiency in static conditions, they also make the system brittle and unable to cope with novel disruptions. In Designing Freedom, he gives a vivid analogy of managers on high poles trying to control subordinates on shorter poles in a chaotic game: adding hierarchy and rules seems to stabilize things and improve order, but it “interferes with [people’s] freedom to do the best they can,” he warned, meaning freedom starts to be subordinated to efficiency under the false assumption that tighter control is always better5. The immediate alternative to some control is indeed chaos – “total anarchy,” as Beer quips – yet the long-term alternative to over-control is equally perilous: stagnation and collapse.

What modern corporations call efficiency often means eliminating slack – treating any idle resources or autonomy as “waste.” Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM), however, emphasizes that slack is not waste but essential spare capacity for adaptation5. Without slack, a firm cannot respond to unexpected spikes in demand, supply chain disruptions, or new opportunities. Beer built on the cybernetic insight known as Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety: “only variety can absorb variety.” In plain terms, a company’s internal flexibility must match the complexity of its environment6. If you squeeze out all flexibility in the name of efficiency, you leave the organization unable to absorb shocks. Many corporate crises illustrate this – for instance, a supply chain optimized to just-in-time efficiency crumbles when a single supplier fails, because no backup options exist.

Human Potential vs. Machine Efficiency: Beer also criticized the way corporate efficiency drives reduce human workers to cogs in a machine. In a traditional top-down enterprise, most employees are given narrow, repetitive roles – they are under-utilizing their human capacities. From a cybernetic perspective, each human is an enormously complex, adaptable system in their own right7. Yet in an “efficient” assembly-line or call center, workers are asked to deploy only a tiny slice of their abilities (e.g. a security guard uses just vigilance and sight; a call-center operator is limited to reading scripted replies)8. This may create a superficially efficient production process, but it wastes potential and breeds alienation. Beer argued that organizations designed to fully engage workers’ intelligence, creativity, and even intuition would not only be more humane but also more effective. In The Heart of Enterprise he notes that “the people cannot eat paper” – i.e. bureaucratic rules and reports don’t feed or fulfill anyone9 – and he urged giving workers the autonomy and information they need to solve problems on the spot. In Chile, he helped set up workplace workers’ councils with real decision-making power, showing that frontline employees often know best how to improve operations if given the freedom and tools to do so10. Such decentralization increases the system’s ability to handle variety, even if it looks “inefficient” to those who expect orders to only flow from the top.

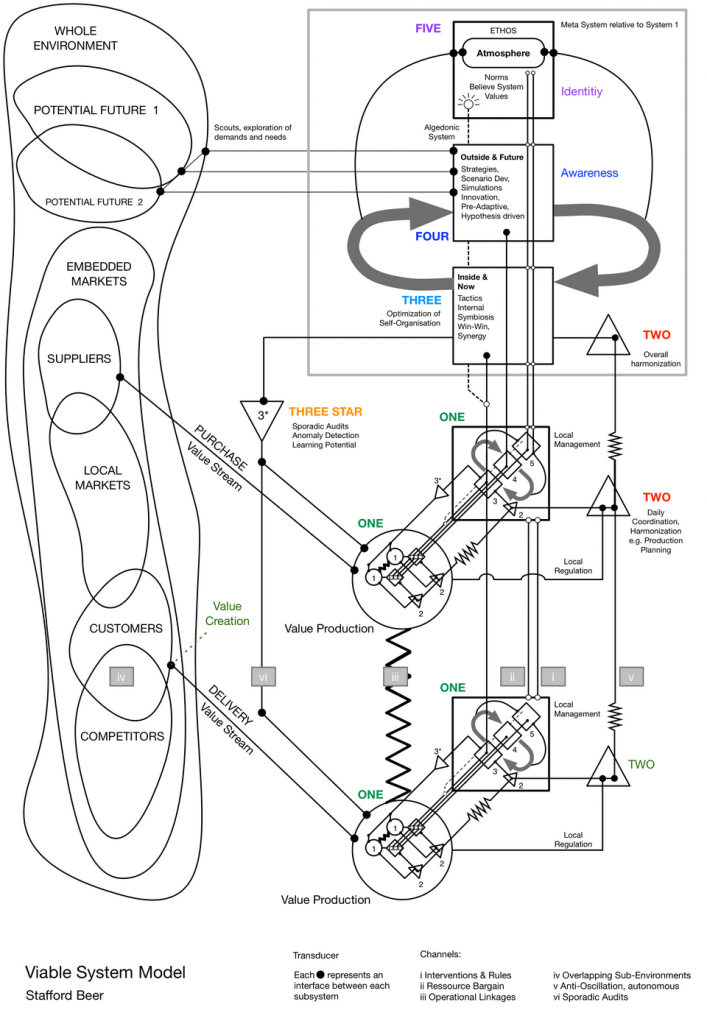

Beer’s Viable System Model formalized this balance between centralized control and distributed autonomy. Every viable organization, he found, has a recursive structure with distinct functions (which he labeled Systems 1 through 5). System 1 units are the operational teams doing the work; they need freedom to respond to local conditions. Higher systems (3, 4, 5) provide coordination, long-term planning, and policy, but should not micromanage the details5. The key is a constant feedback loop between levels: local units report upward about their performance and challenges, while higher management intervenes only when integrated action or global changes are required5. This model contradicts the one-size-fits-all approach of many corporations. It implies, for example, that a “lean” organization with zero buffers and rigid rules might actually be less effective at self-regulation than one that tolerates some improvisation and redundancy. Indeed, Beer observed that overly bureaucratic firms become slow and incapable of innovation, whereas completely laissez-faire organizations can descend into internal chaos11. The sweet spot is an organization that learns and adapts – one that treats feedback as the lifeblood of efficiency12.

Evidence Against the Efficiency Myth: By applying these principles, Beer repeatedly demonstrated better outcomes than traditional methods. His work in the steel industry, for instance, showed that giving more real-time information and decision power to plant managers produced superior results compared to tight central planning by headquarters13. During Chile’s Cybersyn project, factory output was maintained and even improved despite enormous economic turmoil, partly because factories had both the autonomy to adapt and the support of a central telex-based network for guidance in emergencies13. The lesson is that resilience trumps simplistic efficiency. A corporation obsessed with short-term efficiency – quarterly profits, labor cost cutting, etc. – may undermine the very feedback systems and human creativity that ensure long-term survival. Beer’s work provides a scientific basis for this critique: a system optimized to yesterday’s conditions will fail tomorrow. In sum, Beer reframed efficiency as dynamic effectiveness. Instead of asking “How tightly can we ship this quarter?”, he’d ask “How well can we handle whatever the world throws at us?” An “efficient” company in Beer’s terms is one that can navigate complexity and surprise – arguably the only kind of efficiency that matters in a complex, fast-changing world14.

[Below is Beer’s Viable System Model, a schema for balancing control and freedom in a complex organization. The model identifies five interacting subsystems (labeled 1 through 5 in the diagram) present in any viable organization. System 1 units (green, at bottom) are the basic operational elements – e.g. departments or local teams – interacting with the environment (markets, suppliers, customers). Higher-level systems (shown in the meta-system box: Systems 2, 3, 3, 4, 5) represent coordination, audit, intelligence, and policy functions respectively. Arrows indicate information channels for attenuating environmental complexity and amplifying regulatory responses. This model illustrates Beer’s argument that true efficiency comes from an architecture that absorbs variety through layered feedback loops, not from simplistic top-down control.]

Figure: Beer’s Viable System Model (schematic of an organization as a recursive, self-regulating system). Each System 1 is an operational unit with autonomy to manage its local environment; Systems 2–5 form the metasystem that coordinates activities, sets strategy and identity (ethos), and ensures the whole remains viable. The model emphasizes information flows (solid and dotted lines) for communication, amplifiers to boost control signals when needed, and attenuators to filter incoming complexity. This structure allows a company or any complex organization to be both adaptive and stable.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VSM_Default_Version_English_with_two_operational_systems.png2. Dangers of Unfettered Capitalism: Beer’s Warnings

Stafford Beer’s career straddled both corporate consulting and socialist economic planning, giving him a unique perspective on capitalism. While he was not an anti-capitalist ideologue in the traditional sense (he sought practical improvements more than grand manifestos), Beer became deeply critical of “unfettered” capitalism – that is, a capitalist system with little democratic oversight or social guidance. His works illustrate several dangers if market forces and private corporations are left unchecked by ethical or governmental constraints:

- Narrow Goals and “Paper Profits”: In Beer’s view, free-market capitalism tends to prioritize monetary metrics (profit, share price, GDP growth) at the expense of human purposes. He famously introduced the concept of eudemony, meaning human well-being or flourishing, and argued that money should be a means to eudemony, not the other way around: “money is nonetheless an epiphenomenon of a system that actually runs on eudemony… I have come to see money as a constraint on the behavior of eudemonic systems, rather than… eudemony as a by-product of monetary systems,” he wrote4. In a capitalist economy, however, companies and even governments often behave as if human well-being will magically spring from the pursuit of profit. Beer flatly rejects this notion. He points out that capitalism can generate growth and riches while alienating workers and neglecting social needs – a classic case of confusing means and ends. For example, a corporation may report record profits (a sign of “efficiency” in capitalist terms) while its employees and customers suffer – indicating the system is not actually delivering well-being. Unfettered capitalism, Beer argues, externalizes too many costs: pollution, stress, inequality, and other harms are not accounted for on the balance sheet, so the system can look successful right up until it fails catastrophically.

- Unchecked Corporate Power: Beer presciently warned that if new information technologies were controlled solely by profit-driven corporations, the public’s freedom would be at risk. In Designing Freedom, he admonished readers that “the computer is… really their only hope” for managing complex society – yet people’s irrational fear of technology was allowing an “electronic mafia” to take over18. This electronic mafia, as Beer colorfully described it, referred to the emerging class of corporate tech elites. He envisioned (with remarkable foresight) that large tech companies could become an invisible governing force, extracting “protection money” in the form of surveillance data and dominance over daily life19. Today, in the age of Big Tech monopolies, social media algorithms, and ubiquitous surveillance capitalism, Beer’s warning sounds prophetic. He noted that if society did not consciously guide the use of cybernetics for the public good, then corporations or authoritarian regimes would do so for their own ends, effectively “enslaving” people with the very technologies that could liberate them20. Unfettered capitalism, in other words, might harness cybernetic tools (big data, AI, real-time monitoring) to maximize profit and control – treating individuals as mere consumers or data points – rather than to maximize human freedom. We see this today when online behavior is “funneled into easily manageable forms to be better captured by a handful of firms”20, resulting in a loss of privacy and autonomy. Beer’s work in Chile was in part a countermodel: he helped design technology (Cybersyn) aimed at empowering workers and informing democratic government, not just enriching a few shareholders21.

- Instability and Crises: Beer also demonstrated that pure market capitalism, if unregulated, is prone to wild fluctuations and crises – what a cybernetician would call oscillations due to positive feedback loops. For example, speculative bubbles, panics, supply-chain cascades, and “race to the bottom” dynamics all result from components of the economy amplifying each other’s behavior without adequate damping. In Brain of the Firm and Platform for Change, Beer showed how intelligent feedback mechanisms could dampen harmful oscillations. A famous example is the Chilean Opsroom in Project Cybersyn, where economic data from across the country was collected daily and displayed to government managers in real time, allowing early warning of trends (say, a factory slowdown or distribution backlog) and measured responses before things spiraled out of control22. In contrast, capitalist markets often only signal problems after they’ve exploded (e.g. empty shelves or stock crashes), by which time great damage is done. Beer argued that unfettered capitalism’s sole regulator is profit – a crude signal that often arrives too late and ignores social fallout. By the time price spikes indicate a wheat shortage, to use Beer’s example, it might be too late to avert people going hungry19. A cybernetically managed economy could sense and respond to such issues faster, before they become acute. Thus, Beer believed that leaving everything to the “invisible hand” of the market was asking for trouble; active feedback and coordination (i.e. governance) are needed to achieve stability and avoid what we today call “market failures.”

- Erosion of Democracy: Finally, Beer was concerned that capitalism unchecked would erode genuine democracy. If corporations become too powerful, they effectively control policy – directly or indirectly – and citizens lose meaningful input. Beer’s experiences in Chile underscored this: the moment the democratic socialist government of Salvador Allende began to subordinate corporate interests (nationalizing key industries, raising wages), a devastating backlash ensued from domestic business elites and their international allies16. The U.S. government and multinationals colluded to “make Chile’s economy scream” in order to undermine the elected government16. This episode taught Beer that capitalism, when threatened, can act anti-democratically – supporting coups or other anti-democratic measures to preserve its dominance17. In more gradual ways, we see similar tensions in Western democracies today: money in politics, corporate lobbying, and revolving-door corruption all exemplify how unfettered capitalism can hijack the state. Beer’s writings call for transparency and participation to combat this. For instance, he envisioned real-time referenda and feedback systems (like his proposed algedonic meters that citizens could use to signal pleasure or pain with government services) to keep the government responsive to people rather than to special interests. If capitalism concentrates wealth and power into a few hands, such cybernetic feedback from the populace becomes even more crucial to rebalance the system.

In summary, Beer’s work lays out a compelling case that capitalism must be deliberately tamed if we want a stable, free, and humane society. A profit-driven system on autopilot will sacrifice human ends for monetary means, and ultimately undermine itself.

3. A Scientific Materialist Argument for Socialism

One of the most remarkable aspects of Stafford Beer’s legacy is how it bridges the gap between socialist ideals and scientific, materialist methods. Where traditional socialist thought often relied on moral arguments or philosophical claims about class, Beer added the hard-headed rigor of a systems scientist. He sought to prove, through working models and empirical data, that an economy oriented toward social needs (rather than private profit) could outperform and outlast its capitalist counterpart. In doing so, Beer provided a kind of “proof of concept” for socialism grounded in cybernetics.

Cybernetics over Ideology: Beer’s approach to socialism was pragmatic and experimental. He famously got the opportunity to test his ideas in Chile under President Salvador Allende, implementing Project Cybersyn as a real-time economic coordination system for a democratically socialist government. The goal was to show that advanced technology and scientific management could make a planned economy viable, efficient, and responsive1. This was a materialist endeavor through and through – instead of debating theory, Beer and the Chilean team built machines, wrote software, and reorganized factories. At the heart of Cybersyn was Cyberstride, software to forecast factory production, and the Opsroom, an operations room where government ministers could literally see the nation’s economic data updating in real time on wall screens22. This system was designed to solve what economists in the West claimed was the fatal flaw of socialism: the knowledge problem. Friedrich Hayek had argued that no central planner could gather and process the dispersed knowledge that price signals convey in a market. Beer’s answer: use computers and communications networks to gather information faster and more comprehensively than any market price system could8. In essence, Beer attempted to technologically obsolete the Hayekian argument by creating a cybernetic feedback loop for the whole economy.

The Cybersyn experiment, though cut short by the 1973 Pinochet coup, yielded promising results. It helped the Chilean government manage a severe nationwide strike by trucking companies in late 1972: using the network, authorities re-routed trucks and prioritized fuel to keep essential goods moving, blunting the strike’s impact13. Even within its brief lifespan, Cybersyn showed that strategic planning and worker participation could coexist. Beer built mechanisms for worker input – for example, an algorithm to detect when factory workers on the shop floor manually intervened to adjust production, treating those interventions as valuable data (a sign that humans spotted an issue the model missed)22. He also outlined a subsystem called Cyberfolk that would allow the Chilean public to feed their collective mood (satisfaction or unrest) directly to the Opsroom via home devices – a bold attempt at cybernetic democracy. All these were tangible systems, not just theories.

Viability of a Planned Economy: Perhaps the strongest material argument for socialism from Beer’s work is simply this: it can work, if done cybernetically. In the book The People’s Republic of Walmart, authors Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski highlight Cybersyn as a successful prototype, noting that “Cybersyn was successful enough to demonstrate the viability of a planned economy”23. They point out that large modern corporations like Walmart and Amazon essentially do economic planning internally on a massive scale – allocating resources, managing supply chains, setting prices – using advanced data systems, and they do so far beyond the scale of Chile’s 1970s economy23. In other words, planning works every day within corporate giants; the real question is why those techniques could not be applied in the public sphere for the benefit of all. Beer made the same point decades earlier: a socialist state enterprise can be run with the efficiency and adaptability of the best-run company, provided it has the right informational tools. What Beer added was an emphasis on decentralization within the planned framework. Unlike the Soviet Union’s hyper-centralized model (which Beer criticized for its sluggishness), he implemented a federated model – factories had local autonomy to make decisions, with Cybersyn stepping in mainly to alert the government of serious anomalies or to coordinate resources across factories8. This resembles a socialist economy functioning like a network of cooperating firms rather than a single monolith. It’s scientific socialism in practice: test, iterate, use data.

Automation and Beyond: Beer’s socialism was also “materialist” in looking beyond human labor as the sole economic driver. He anticipated a future where automation and information technology could free humans from drudgery. In Designing Freedom, Beer argued that the advances in computing and communications had to be harnessed for liberation, not just productivity18. He saw potential for planned automation to shorten the workweek and involve people more in decision-making and creative pursuits. This aligns with a socialist vision where the economy exists to deliver a good life for all, not to maximize profit for a few. Beer even engages with Marxist concepts: he effectively sees cybernetic planning as a way to overcome the alienation of labor under capitalism. In a telling passage, Platform for Change contrasts eudemony with Marx’s alienation: under capitalism, work estranges people from their true selves, whereas under a eudemonic (cybernetic socialist) system, work and society would be structured to “give workers their lives back to fulfill their humanity”24. This isn’t sentimental utopianism; it’s a design goal, to be achieved by science-led restructuring of institutions.

Scientific Rigor and Evidence: Another component of Beer’s materialist argument is the use of evidence and feedback to guide policy – essentially applying the scientific method to social governance. In Chile, the Cybersyn team continuously monitored key performance indicators of the economy (production rates, inventory levels, absenteeism, etc.) and could run simulations of economic scenarios25. This meant socialist planners could catch errors and learn, rather than make grand 5-year plans and pray they work. Beer proposed that instead of dogma, socialist economies should operate with continuous hypothesis testing: try a policy, measure outcomes, adjust accordingly (what today might be called an agile approach to governance). This is a sharp break from both the inflexible command economies of the past and the laissez-faire “just trust the market” stance of neoliberalism. It represents a third way: scientific governance for the common good. Beer even wanted to involve the public in this feedback cycle via the algedonic signals – effectively treating public contentment as a crucial output metric of the system26. If that could be quantified and fed into decision-making, a socialist government would have a real-time pulse of its people’s welfare, creating a more responsive, evidence-driven administration.

To summarize Beer’s case for socialism: it wasn’t based on abstract morals but on practical cybernetic engineering. He demonstrated that an economy can be democratically planned and dynamically managed with the help of computers, communications, and a proper organizational model. Such an economy can avoid the pitfalls of both Soviet-style over-centralization and capitalist chaos. It can unleash human creativity (by removing the profit shackles and alienating management practices) and use machines to handle complexity and routine tasks. Beer’s socialism is one where the economy serves humanity, guided by what our measurements tell us will maximize human freedom and development. In a sense, it aligns with what modern observers call “fully automated luxury communism” or the idea that technology makes it possible to provide abundance for all – but Beer adds the governance framework to actually make it work without falling into tyranny or disorder. His work stands as a blueprint for a humane planned economy, grounded not in wishful thinking but in systems theory and real-world prototyping. It invites us to imagine what a nation or the world could achieve if we designed our economic system for eudemony.

4. Cybernetic Governance: Designing a Democracy that Controls Corporations

Stafford Beer’s insights were not limited to corporate or national economic management; they also extend to the very structure of governance. At the core of Beer’s political thinking is the idea of the Viable System applied to society: government should be organized in a recursive, cybernetic way to amplify citizens’ voices and attenuate the complexity of modern society into manageable information. In practical terms, Beer envisioned governmental systems where local, state, and federal levels are linked by continuous information flows (not just top-down commands or occasional elections), and where corporations and other powerful institutions are firmly embedded within and regulated by this democratic metasystem.

Let’s break down how Beer’s work could be applied to American governance across local, state, federal, and corporate domains, and what structures would ensure corporations remain subordinate to democratic government:

- Recursive Levels of Government (Local → State → Federal): Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM) suggests that large systems work best when organized in recursive layers, each autonomous in its sphere yet accountable to the larger whole1. We can map this to American governance: municipal governments (towns, cities) as the System 1 units doing “primary operations” (delivering services, maintaining order in their community), state governments as a mid-tier coordinating multiple cities/counties (analogous to System 3 in VSM, overseeing and allocating resources among local units), and the federal government as the higher-level systems (Systems 4 and 5 in VSM, providing long-term strategy, research, inter-state coordination, and overall policy ethos). The key structural change from the status quo would be to create much tighter feedback loops between these levels. In Beer’s prototype designs, every level receives real-time information from the level below and supplies guidance to it in return. Higher levels set broad policy and intervene only to coordinate or help solve problems that exceed a local unit’s capacity, rather than micromanaging everything. This aligns with Beer’s insistence that local autonomy be preserved even within a planned system10.

For example, imagine a National Opsroom for the U.S. federal government where a dashboard shows key performance indicators from every state – economic data, health metrics, environmental readings, etc. – updated perhaps daily or weekly (today this is technically feasible via the Internet of Things and data analytics). Likewise, each state could have a similar control room aggregating data from its counties and cities. This sounds technocratic, but Beer insisted it must be democratic technocracy: the information should be open and understandable to the public, and used by elected officials and civil servants to make evidence-based decisions in the public interest. Importantly, local autonomy is preserved. In Beer’s model, higher levels should not micromanage lower ones; instead, they set broad policy and intervene only when needed for coordination or to address issues beyond a local unit’s scope. “Government is the people’s help,” Beer liked to say – meaning the role of higher government is to assist lower levels, not hinder them27.

We see glimpses of this recursive approach in practice (for instance, the way U.S. states coordinate disaster response with FEMA, or federal funds flow to states for highways), but Beer would push it much further with formal cybernetic structures. The System 2 function in VSM – smoothing coordination between units – might correspond to standard protocols or agencies that ensure, say, neighboring cities or states can easily share information and resources, avoiding bureaucratic silos.

- Citizen Participation and Feedback: A hallmark of Beer’s vision for governance is continuous two-way communication between the people and their government – far beyond infrequent elections or opinion polls. He believed that modern technology allows a form of direct democratic feedback that earlier societies couldn’t manage28. In Chile, he proposed a network of telex machines to gather public input and even experimented with an idea where citizens could turn a dial in their home to signal satisfaction or dissatisfaction (the algedonic meter)29. Applied today, this could take the form of secure digital platforms where citizens vote or express preferences on local issues in real time, which are then aggregated for officials to respond to. We see early versions of this with e-government petitions, online town halls, participatory budgeting apps in some cities, etc., but Beer’s concept was more systemic. He imagined something like a “Liberty Machine” that continuously converts millions of individual inputs into actionable knowledge for government30. (The phrase is his: in Designing Freedom, Beer spoke of building a “Liberty Machine” to create liberty – meaning a system that treats society “not as an entity characterized by more or less constraint, but a dynamic viable system that has liberty as its output”21.) This startling redefinition implies that freedom isn’t simply the absence of government interference (the traditional view), but rather the product of a well-designed governing system. In other words, a cybernetic democracy would use regulation and feedback such that the end result is maximal liberty for individuals, consistent with the collective good. For example, if people are constantly informing local authorities about their neighborhood needs and preferences, the local government can act on those signals to improve quality of life (fix issues, provide desired services) – effectively increasing citizens’ freedom to live as they wish.

- Government as “the People’s Help”: In Chile, Beer articulated five principles of what he called “eudemonic government,” essentially design rules for a government that truly serves its people31. The first principle was “Government is the people’s help.” This seems obvious, but in practice bureaucracy often makes government feel like an obstacle instead. Beer insisted on structures that make government assistance immediate and accessible. For instance, he advised setting up one-stop local service centers where any citizen could contact an official and get help right away without being bounced around – “helping now” was the second principle32. To achieve this, he designed scalable recursive structures of public service: each local official handles a manageable load of issues, and if something is beyond their scope, it escalates clearly and quickly to the next level33. In American governance, this could translate to, say, a tiered system of ombudsmen: neighborhood stewards who can resolve perhaps 80% of issues on the spot (from potholes to paperwork troubles), district officers who handle tougher ones, and state/federal liaisons for the most complex. The idea is that no problem falls into a black hole; responsibility is always clearly owned at some level. (Beer’s quip “The people cannot eat paper” was a rebuke of red tape – paperwork and formality that fail to translate into real help9.) In a cybernetic government, paperwork and endless forms would be minimized by smart design (e.g. pre-filled data, interoperability between agencies – things that our current tech actually allows).

The third principle was transparency of process: “The road to help has signposts.” People should know who in the government is handling their issue and what the status is. Modern IT systems, again, could enable this (imagine tracking your permit application like tracking a package). The fourth principle was humanizing government: “Help is a name and a face.” Beer wanted officials to take personal responsibility for solving an issue, rather than citizens receiving anonymous form letters. This fosters trust and accountability. The fifth principle was future-orientation: “The future starts today.” Don’t just patch the current crisis; think of long-term effects on future generations. If we embed these principles, the structure of governance becomes far more responsive and user-friendly – a stark contrast to the alienating bureaucracies that cause people to lose faith in government34.

- Keeping Corporations Subordinate: Now, how do we ensure in such a system that corporations remain subordinate to the democratic government and not vice versa? Beer’s framework offers multiple structural safeguards:

- Constitutional & Legal Metasystem: In VSM terms, the government (particularly at the federal level) is the System 5 – the source of overall policy and identity for society (it sets the “ethos” and norms). To keep corporations in check, the laws and constitution must clearly define the purpose of corporations as serving the public good under the oversight of democratic institutions. For instance, corporate charters could be periodically reviewed by public authorities to assess if the corporation is still aligned with societal goals (a practice that, in early American history, existed but faded away). Regulations must have teeth: System 3 in VSM corresponds to regulatory enforcement and resource bargaining. In governance, this means a strong regulatory state with agencies that have real-time data on corporate activities (especially large firms that impact millions) and the ability to enforce laws. With modern tech, regulators could receive continuous feeds of information (with appropriate privacy safeguards) from companies rather than waiting for annual reports or whistleblowers. This is akin to how Beer set up monitoring via Cybersyn for Chile’s nationalized firms29 – a democratic government today might require big corporations to provide dashboards of environmental emissions, labor conditions, etc., directly into a public Opsroom. If something goes out of bounds (say, a factory’s pollution exceeds limits or a bank takes on excessive risk), an algedonic signal (an alert for pain) is triggered for regulators.

- Institutionalized Counterweight: Beer would likely advocate for formal “anti-corporate” subsystems – not anti- in the sense of hostile, but as balancing forces. For example, empowered labor unions or workers’ councils can act as an internal regulatory network within corporations, feeding back information and pushing back against purely profit-driven decisions. In Chile, Beer worked with interventors – teams of scientists and workers who helped run factories democratically and reported both to the workforce and the government35. A modern equivalent might be works councils (common in some European countries) and co-determination boards that include worker and community representation in corporate governance. By embedding such stakeholder feedback, corporations are less likely to go rogue against the public interest. From a VSM perspective, one could say corporations themselves should be treated as System 1 units of the economy, and the government’s job (as System 3/4/5) is to continuously audit and guide them so that their activities align with the overall goals of the nation36. Beer even created a concept of System 3*** (three-star) for independent monitoring of operations – analogously, an independent audit body that inspects corporations’ compliance (like a super-charged GAO or an empowered SEC with cybernetic tools) could be institutionalized12.

- Variety Alignment via Law: Recall the Law of Requisite Variety – regulators must have as much variety as the entities they regulate. This means governments need expertise and adaptive capacity to match giant global corporations. One structural solution is to invest in public sector technology and talent. Beer’s work in governance insisted that government must keep pace with complexity; it needs its own sophisticated systems and models to oversee the economy. For example, regulators might employ AI and data analytics (the way corporations do) to detect emerging risks in financial markets or supply chains. This also suggests an international dimension: today’s megacorporations operate across borders, so nations may need to coordinate (a “metasystem” above the national level) to regulate effectively. Beer hinted at this in later writings, suggesting that viable systems at the national level might eventually need to coordinate on a planetary level to handle global problems (climate, multinational corporations, etc.)39.

In essence, Beer’s cybernetic governance model would hard-wire democracy, feedback, and accountability into the structure of government itself. It would ensure that corporations—important though they are for innovation and production—remain servants of society, not its masters.

5. Updating Beer’s Vision for the 21st Century

Stafford Beer was astonishingly ahead of his time, but he was still working with the tools and context of the mid-20th century. The world has changed significantly since Beer’s major works were published. Technology has advanced by leaps and bounds – we have the internet, personal computers everywhere, smartphones, artificial intelligence, and vast data centers. Politically, the Cold War bipolar world that framed much of Beer’s writing has given way to a more complex multipolar (or even fragmented) scenario, with neoliberal capitalism the dominant mode (though now facing new challenges). Economically, globalization and financialization have created new forms of complexity that Beer only glimpsed. To keep Beer’s ideas relevant, we should consider what needs updating or refining today:

- Modern Technology – Both a Blessing and a Curse: Perhaps the most obvious update is that the technological impediments Beer faced are largely gone. In the early 1970s, Beer had to make do with one mainframe computer in Chile (an IBM machine running Cyberstride) and a network of telex machines to transmit data1. Today, even a cheap smartphone has more computing power than that entire setup, and networks transmit data globally in milliseconds. This means that Beer’s more ambitious proposals – like real-time economic control, direct democracy feedback loops, and dynamic modeling of society – are far more feasible. For example, Beer’s dream of an algorithm that could balance supply and demand across an economy in real time is essentially an instance of what we now call big data analytics. With cloud computing, one could crunch enormous datasets about production, consumption, and logistics continuously. The growth of AI and machine learning also offers tools Beer didn’t have for pattern recognition and prediction in complex systems. In fact, some recent analyses explicitly use Beer’s lens to discuss AI: for instance, seeing AI as a powerful tool for variety engineering (managing complexity) in governance43.

However, these technological advances also introduce new challenges that Beer only speculated about. One is the centralization of data. Beer might not have foreseen just how much data (and power) would be concentrated in a few private hands (think Google, Amazon, Facebook servers). In updating Beer’s vision, we must address data governance: any cybernetic socialist system or smart democracy will rely on large amounts of information. Ensuring that this information is not monopolized or used oppressively is crucial. Beer’s ethic suggests that such data should be treated as a public good (or at least heavily regulated). For instance, we might institute public data trusts or require that certain kinds of socially generated data (like mobility patterns in a city, or aggregate consumer needs) be fed into open platforms accessible to planners, communities, and researchers, not just locked in corporate vaults. Additionally, privacy protections would need to be far stronger in any modern implementation of Beer’s ideas. In his time, concern about surveillance was already present (he noted people feared computers as “malign” influences)5, but today the threat is far greater. We’d need to update Beer’s models with encryption, anonymity where appropriate, and democratic oversight of any surveillance to prevent abuse. In short, technology has caught up to Beer, but we must use it wisely. As one commentator put it, Beer’s vision can now be realized through digital twins and ontologies – e.g. we can create a real-time digital twin of an economy or a city for planning purposes – yet this also demands robust safeguards and inclusive control to avoid new forms of tyranny43.

- Complexity of Global Systems: Another update is acknowledging the increased complexity and interconnectedness of global systems. Beer saw the need for coordination beyond the nation-state – he worried about “planetary viability” in the 1970s and advocated for institutions that could handle global issues. Today’s problems like climate change, pandemics, and financial crises underscore that any viable system of governance must extend internationally. We might extend Beer’s model to propose, for example, a Global Viable System where nations themselves share feedback and control mechanisms for issues that transcend borders. Institutions like the United Nations or new entities (say, a Global Climate Authority) could be re-imagined along Beer’s lines: participatory, adaptive, with clear recursive structures. This is speculative, but updating Beer means not shying away from scale. He was bold about scale – he even wrote that the old debate of “government vs. liberty” was outdated; the real task was designing effective systems that deliver liberty39. In the 2020s, the scale is planetary.

- Political Realities and Implementation: Beer was an idealist but also a pragmatist when it came to implementation. Updating his ideas requires grappling with political obstacles. Many of Beer’s proposals (like real-time economic management or direct democracy tools) run up against entrenched power structures and ideologies. For example, powerful interests may resist real-time transparency or democratic oversight of corporate data. Thus, any update must include strategies to build public understanding and demand for these cybernetic reforms. Beer’s work was often technical; translating it into plain language and concrete benefits that citizens can rally around is crucial39. The good news is that many of Beer’s once-radical ideas are re-emerging in modern discourse. Concepts like participatory budgeting, “doughnut economics” (which sets social and ecological boundaries for economic activity), platform cooperatives, and civic tech all resonate with Beer’s vision of a cybernetically steered economy serving human needs. Even the resurgence of interest in “cybersocialism” – through books like People’s Republic of Walmart and Evgeny Morozov’s podcast The Santiago Boys – shows that Beer’s pioneering work in Chile is finally getting its due recognition4041. Scholars and activists are looking at how to apply those lessons with today’s technology and political reality. For example, the idea of using Walmart’s logistical algorithms for public food distribution in a crisis is essentially Cybersyn with cloud computing32.

In conclusion, most of Beer’s core principles stand the test of time: the need for feedback, the balance of autonomy and control, the focus on human well-being, and using science to inform governance. What changes are the tools at our disposal (vastly improved) and the context (new threats and possibilities). Beer’s work should be seen as a living toolkit. It encourages us to constantly ask: Does our current system have the necessary feedback loops? Is information flowing where it needs to? Are we keeping our values (like freedom, equity) as the explicit “output” our system optimizes? If not, how can we redesign it?

One encouraging sign is that many of Beer’s once-radical ideas are indeed re-emerging in practice and discourse. The task of our generation is to pick up the thread and weave it into the fabric of society. Beer’s books were titled with organs and lifeblood – Brain of the Firm, Heart of Enterprise. It’s fitting, because he ultimately was trying to give modern society a brain and a heart commensurate with its body. Our corporations have become like giants, our economies like raging metabolisms; we need brains and hearts in our governance to match them. Stafford Beer’s legacy is the insight that this is possible – that we can design freedom and enterprise with a heart, if only we dare to apply what science has taught us about systems.

By synthesizing Beer’s work and those building on it, this article has sketched how we might answer five crucial questions about efficiency, capitalism, socialism, governance, and modern challenges. The answers point to a common conclusion: we should cyberneticize democracy and the economy – not in the sense of turning decisions over to machines, but in using machines and models to empower better human decisions. The payoff would be a society more aligned with human needs and more resilient to shocks. That is the prize that Beer urges us to claim. As the world grapples with crises that traditional methods seem unable to solve, Stafford Beer’s ideas shine like beacons – guiding us toward a future where freedom and organization, individuality and society, technology and humanity, are not opposites but partners in creating the best possible lives for everyone.

Footnotes:

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Munger discusses Beer’s view of cybernetics as “the science of effective organization,” and contextualizes Beer’s approach in modern terms.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber (blog), September 26, 2023; and ibid., “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Accounts of Beer’s career from optimizing corporate systems in the 1950s to leading Chile’s Cybersyn project in the early 1970s.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber (blog), September 26, 2023. (Highlights Beer’s humanist vision that technology should enhance human freedom rather than restrict it.)

- Stafford Beer, Platform for Change (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1975), 170–71. (Beer’s “manifesto” on society, where he introduces the concept of eudemony and argues that money must be subordinated to human well-being.)

- Stafford Beer, Brain of the Firm, 2nd ed. (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1981). (Beer introduces the Viable System Model and the importance of slack and feedback for true efficiency.)

- Doug Belshaw, “Only Variety Can Absorb Variety,” Open Thinkering (blog), June 19, 2024. (Explanation of Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety in plain terms: a system’s internal flexibility must match environmental complexity.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Describes Beer’s view of each human as a complex system with vast capacities that are often underutilized in rigid organizations.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Illustrates how corporate structures force workers to use only a small fraction of their abilities, e.g. guards and call-center staff limited to narrow tasks.)

- Stafford Beer, Brain of the Firm, 2nd ed. (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1981), 299. (Origin of Beer’s quote “the people cannot eat paper,” emphasizing that bureaucratic paperwork does not nourish or satisfy human needs.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Details Beer’s work in Chile setting up worker councils and giving frontline workers real decision-making power.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (On Beer’s observation that overly rigid, “lean” firms become incapable of innovation, whereas completely laissez-faire ones descend into chaos—implying an optimal balance is needed.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (On Beer’s emphasis that a learning, adaptive organization—supported by layered feedback loops—is more truly efficient than a top-down controlled one.)

- Eden Medina, Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011). (Definitive history of Project Cybersyn; documents that the system helped maintain factory output during turmoil, e.g. mitigating the 1972 truckers’ strike.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber, September 26, 2023. (Emphasizes Beer’s reframing of efficiency as dynamic effectiveness and resilience, contrasting it with short-term profit focus.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Reinforces Beer’s critique that optimizing for yesterday’s conditions or metrics will lead to failure in tomorrow’s environment.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Recounts how domestic and international capitalist forces colluded to “make Chile’s economy scream” in response to Allende’s policies.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Explains Beer’s takeaway from the Chilean coup: when threatened, capitalism can act in anti-democratic ways, supporting coups or undermining democracy to preserve itself.)

- Stafford Beer, Designing Freedom (Toronto: CBC Learning Systems, 1974). (Beer’s CBC Massey Lectures, where he warns against technophobia and introduces the notion of an “electronic mafia” seizing control of technology if the public shies away from it.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Discusses Beer’s “electronic mafia” metaphor and how he foresaw tech corporations exerting quasi-governance through control of digital infrastructure and data, effectively extracting “protection money” via surveillance.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Notes Beer’s warning that without democratic guidance, cybernetic tools would be used by corporations or authoritarians to effectively enslave people; also quotes the observation that online behavior is funneled into capturable forms by big firms.)

- Stafford Beer, Designing Freedom (Toronto: CBC, 1974). (Beer’s concept of a “Liberty Machine” – a cybernetic system designed to output liberty for society; Beer defines freedom as the output of a well-designed system rather than mere absence of restraint.)

- Eden Medina, Cybernetic Revolutionaries (MIT Press, 2011). (Describes the design and function of the Cybersyn Opsroom and its role in providing real-time feedback for Chile’s economy, addressing the knowledge problem and aiding in crisis response.)

- Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski, The People’s Republic of Walmart (London: Verso, 2019). (Argues that Beer’s Cybersyn demonstrated the viability of economic planning; points out that corporate giants like Walmart practice internal planning at immense scale.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Quotes Beer’s Platform for Change on eudemony vs. alienation: capitalism alienates, whereas a cybernetic socialist system would restore human fulfillment.)

- Eden Medina, Cybernetic Revolutionaries (MIT Press, 2011). (Documents how the Cybersyn team in Chile continuously monitored economic indicators and ran simulations, embodying Beer’s ideal of evidence-driven governance.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber, September 26, 2023. (Notes Beer’s idea of involving the public via algedonic meters and the need for translating cybernetic governance concepts into accessible reforms in modern contexts.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Discusses Beer’s five principles for “eudemonic government,” including “Government is the people’s help” and other design rules for a citizen-centered government.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber, September 26, 2023. (Highlights Beer’s vision of using modern technology for continuous citizen-government communication far beyond periodic elections.)

- Nick Serpe, “Liberty Machines and Dark Tech,” Dissent, September 11, 2023. (Interview with Evgeny Morozov on The Santiago Boys podcast, mentioning Beer’s experiments like the algedonic meter and the broader implications of citizen feedback systems in governance.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber, September 26, 2023. (Refers to Beer’s concept of a “Liberty Machine” and how it reframes freedom as an output of a dynamic system that actively incorporates public input.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Summarizes Beer’s “eudemonic government” principles as articulated during the Chile project.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Details Beer’s advocacy for one-stop service centers and immediate government assistance – “helping now” as a core principle of governance design.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Describes the recursive public service structures Beer proposed – issues escalating clearly to higher levels when needed – to ensure no citizen’s problem is neglected.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Covers Beer’s principles of transparent process, personalizing government help, and future-oriented planning, which together make government more user-friendly and trustworthy.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Discusses Beer’s work with interventors in Chile – integrating workers and scientists in factory management – as a model for balancing corporate power from within.)

- Jeremy Gross, “Stafford Beer: Eudemony, Viability and Autonomy,” Red Wedge Magazine, February 18, 2020. (Mentions Beer’s suggestion of a “System 3**” for independent audits – analogous to empowering regulatory bodies to continuously inspect and guide corporate behavior.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Describes how modern computing power and networking make Beer’s ambitious real-time governance ideas technically feasible, but also raises the need for data to be treated as a public good.)

- Kevin Munger, “Tipping the Scale,” Real Life, March 24, 2022. (Highlights Beer’s early awareness of surveillance concerns and the need to update his models with robust privacy and data-governance measures in today’s context.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber, September 26, 2023. (Notes Beer’s view that effective systems delivering liberty render old debates obsolete, and emphasizes translating Beer’s ideas into contemporary movements and language.)

- Kevin Munger, “The Tragedy of Stafford Beer,” Crooked Timber, September 26, 2023. (Observes the renewed interest in “cybersocialism” and Beer’s legacy through works like People’s Republic of Walmart and Morozov’s The Santiago Boys, indicating Beer’s ideas are gaining recognition.)

- Nick Serpe, “Liberty Machines and Dark Tech,” Dissent, September 11, 2023. (Provides context on Evgeny Morozov’s The Santiago Boys podcast and its exploration of Beer’s work in Chile, reflecting a modern reassessment of Beer’s contributions.)

- Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski, The People’s Republic of Walmart (London: Verso, 2019). (Phillips and Rozworski argue that techniques used by Walmart and other corporations could be repurposed for public good—essentially updating Beer’s Cybersyn idea with today’s corporate logistics systems.)

- Nick Swanson, “Stafford Beer and AI as Variety Engineering,” AI Policy Perspectives (blog), October 23, 2024. (Review of Dan Davies’s work applying Beer’s cybernetics to modern AI governance and polycrisis, showing how Beer’s models are informing current thinking on complex system management.)