What Could Have Been: Chains Unbound

The first in a series of “what if’s…” that critically examine American history.

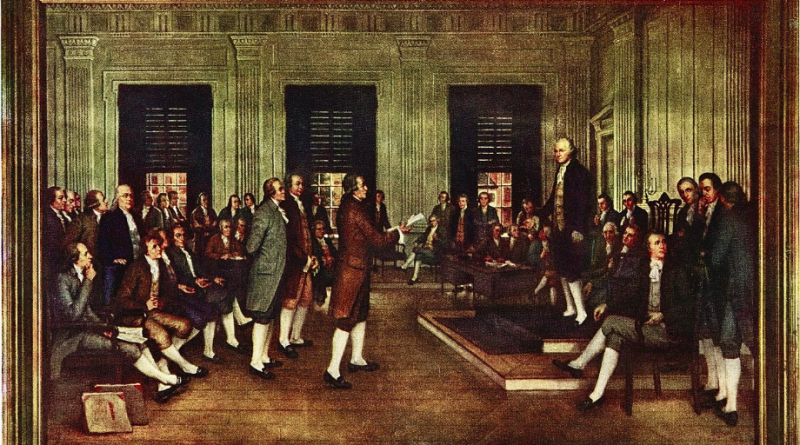

Philadelphia, Summer of 1787. The Constitutional Convention is in session.

The Constitutional Convention was a gathering of some of the brightest minds in the newly formed United States. The air was thick with anticipation, but also tension. The question of slavery, the dark shadow that had loomed over the colonies for centuries, was at the forefront of the debates.

Benjamin Franklin, now in his eighties and a staunch abolitionist, took the floor. “Gentlemen,” he began, his voice firm, “we stand at the precipice of history. We can either build a nation on the principles of liberty and equality or continue the hypocrisy of proclaiming freedom while binding our fellow men in chains.”

James Madison, known for his meticulous notes and sharp intellect, echoed Franklin’s sentiments. “If we are to form a more perfect union,” he argued, “it cannot be one that tolerates the institution of slavery.“

The Southern delegates, many of whom were slaveholders, were outraged. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina warned, “If you demand the end of slavery, you risk the dissolution of this fragile union before it even begins.”

But a new generation of leaders, including a passionate Alexander Hamilton, countered with fervor. “Better to fracture now on the principles of liberty than to sow the seeds of a greater conflict in the future,” Hamilton declared.

The debates raged on for days. Then, George Washington, who had remained silent, stood up. The room fell silent, every eye on the revered general. Washington, a slaveholder himself, spoke of a vision he had, where his own slaves stood beside him, not as property, but as free men and women. “I cannot lead a nation,” he confessed, “where all are not free.”

His words were a turning point. The framers drafted a new clause, calling for the gradual emancipation of slaves and compensation for slaveholders. The clause also provided for the education and integration of freed slaves into society.

The decision was not without consequences. South Carolina and Georgia threatened to secede. But the combined diplomatic efforts of Franklin, Madison, and Washington, along with economic incentives, eventually brought them into the fold.

The United States emerged not just as a new nation, but as a beacon of hope, showing the world that liberty and equality were more than just words on paper.

Over the next decades, the country faced challenges in integrating freed slaves and addressing racial prejudices. But without the institution of slavery casting a dark shadow, innovations and collaborations flourished between races. The nation’s growth was exponential, both economically and culturally.

By the time the 19th century rolled around, the United States, free of the shackles of slavery from its inception, stood as a united front, leading the world in the fight against colonialism and oppression.

In this alternate history, the decision to confront the evil of slavery head-on at the nation’s founding paved the way for a more just, equitable, and prosperous America. The legacy of the framers was not just a constitution, but a nation truly built on the principles of liberty and justice for all.